Commerce and football – never the best of companions, particularly in leagues still struggling to establish themselves in a nation’s hearts. New York Red Bulls, anyone? The subject is a live one in Shanghai, as Shenhua’s new owners face an uncertain situation having discarded the name in favour of their own brand, then apparently agreeing to hand it back again. With it goes the recognition of one of only three teams that can claim to bear the same title since professionalization in 1994. Beijing Guoan and Henan Jianye are now the sole representatives with a name that could lay any claim to a history.

One can argue this is merely symbolic of the era in which these leagues are founded. History continues to cling to European counterparts, despite every attempt from owners to extricate themselves from such inconvenience. A club like Shenhua, founded with a sponsor in the title, never really had a chance – their identity sold before the team even stepped out. As such, from a strictly business sense it’s certainly reasonable enough to understand a new owner wanting to re-brand the team in their own image, discarding that of a sponsor from 20 years previous.

But why is football in China still failing to make much of a connection with the local populace? The stadiums in Shanghai are full only for the visit of European superclubs in pre-season friendlies – football lives here, but passion burns not for the throwaway merry-go-round of the local sides. It pays to not get attached to a local team, for who knows when they will relocate, rebrand or switch colours?

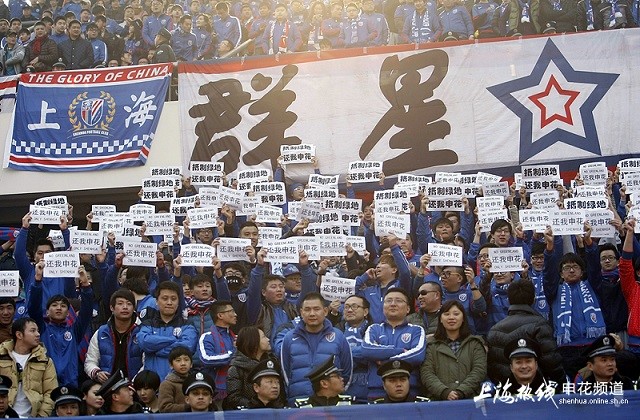

It’s hard to imagine the CSL or MLS ever making major inroads while these factors remain. So, yes – it’s just the replacement of a sponsor’s name, but the betrayal felt by fans for whom that was their name just adds to the ever-growing list of reasons not to care about Chinese football as a whole. With match-fixing episodes still fresh in the memory, and a general distrust of the authority figures in charge, it’s not hard to see why faraway teams, with their established geographies and identity, make a more attractive proposition.

Perhaps Chinese football is ahead of the curve. As the rest of the world adjusts to an era of top-tier clubs being nothing more than playthings of the super-rich, China is already there – commoditization at its purest. Branded stadiums, approved drinks partners, and even a team name for sale at the right price.

But where does this world leave supporters? In China, accessibility at least remains excellent – ticket prices being affordable to all (a season ticket at Shenhua costing around a third of one month’s salary even at minimum wage), but this by definition means fan protest is of limited impact. Even Manchester United struggle to fill a stadium for minor games following 55% price increases under Glazer ownership – such problems are certainly capable of forcing an owner’s hand. Shenhua, to all extents and purposes, could play to an empty stadium every week with little to no financial repercussions. But, again, to look at the smaller figures is to miss the wider point – football as a whole has no traction without a population that cares for it; the TV deals and sponsorship pumping billions into the game elsewhere reliant on a product that captivates. The sport taking root in China appears ever more distant in a league of disembodied corporate teams floating around a vast and detached country.

Ultimately, though – success speaks louder than any history. It’d be tough to find many at Guangzhou Evergrande or Manchester City lusting for the days before the money rolled in, and it’s difficult to associate the prominence of Borussia Dortmund jerseys in China with any kind of long-term love affair. There was a time when even a club as steeped in history as Liverpool welcomed single-party ownership with open arms, only to embrace years of disaster. But who knows – if Greenland’s era at Shanghai goes in the Evergrande direction, maybe one day people will look back and wonder what all the fuss was about. What’s in a name, anyway?